THE HISTORY OF THE ARMY

The first efforts to organise a regular army (1821-1831)

The history of the Hellenic Army is inextricably interwoven with the history of the Hellenic Nation.

The need to establish a regular army came about upon the declaration of the revolution. The philhellenes foreign military men contributed greatly to this effort.

The forerunner of the regular corps was the “Sacred Band” which was established by Alexandros Ypsilantis in Iasi of Moldavia and Wallachia. Most of its men fell heroically in the Battle of Dragasani. In the same standards, Dimitrios Ypsilantis with a group of expatriates and philhellenes, established in Kalamata a regular corps, equal to half a battalion and an artillery detachment under the leadership of the French Major Baleste. The Corps took part in the Siege of Tripolitsa, the occupation of Nafplio and the Acrocorinth and it was disbanded in late January 1822. The A’ National Assembly, through the resolution “Regarding the Organisation of the Army”, decided to establish the first Arms: those of Infantry, Cavalry, Artillery and Engineer. Thus, the first Infantry Regiment was established, consisting of many philhellene officers, while the command was assigned to the Italian Colonel Tarella. The Regiment participated in a campaign in western Greece and it was almost completely destroyed in the Battle of Peta.

With the disbursement of the loans, a new effort was taken up to establish a regular corps. With the

enlistment of volunteers, a battalion was formed, approximately 500 men strong, under Colonel

Panagiotis Rodios, while at the same time an artillery detachment was formed under Olivier Voutier.

In 1825, the French Colonel Charles Favier assumed the command, forming two battalions, approximately 400 men strong each. With the new law regarding the recruitment and enlistment of numerous volunteers, its force reached 4.000 men. Four infantry battalions, three cavalry squadrons, a battery and a light infantry detachment were formed. In March 1826, one of its detachments took part in the Siege of Karystos, while in August of the same year it participated in the Battle of Chaidari. Its most heroic action was breaking through the enemy lines, during the Siege of Acropolis and resupplying the garrison with men and ammunition.

The arrival of Kapodistrias inaugurated a new period in the organisation of the regular army. In 1828 he set up the ‘War Council’ as an advisory body, while the following year he established the ‘Secretariat for Military and Naval Affairs’ (Ministry of War). At the same time, he devoted himself to the reorganization of the irregular troops, with the ‘Organization of the Chiliarchies’. These divisions participated in the clearing operations in the Sterea, and after the last battle of the revolution they were disbanded and gradually reorganized into thirteen light infantry battalions. The replacement of Favieros by the Bavarian Colonel Karl Heideck, the formation of the first artillery battalion, the organization of the curatorship and, finally, the establishment for the first time of an engineering department, marked the main organizational actions of the Governor. The culmination of his actions was the establishment of the “Company of Evelpidon” in July 1828 in Nafplio and its replacement in January 1829 with the “Central War School”, which was the precursor of the present Military School of Evelpidon.

The first Greek regular corps was formed by Alexandros Ypsilantis, on 3 March 1821, in Iasi of Moldavia and Wallachia, called “Sacred Band”. Throughout the year 1823, the reorganisation of the

Regular Army proved impossible, for strictly financial reasons. Only in July 1824, with the conclusion of a loan agreement with England, were the obstacles surpassed and the Government moved forward with the re-establishment of the Regular Army.

The Army in the years of King Otto (1831-1863)

The assassination of Kapodistrias had immediate consequences for the troops too. The light battalions disbanded, forming armed groups, while the few existing units could not guarantee defence and security.

Otto arrived in Greece in 1833, accompanied by a Bavarian garrison approximately 4.000 men strong

and the Regency, which immediately moved forward with reformation actions for the regular army.

One of the first decrees was the resolution of the “New Army Organisation”, which stipulated the

composition and the force of the troops as follows: Infantry, consisting of eight Battalions. Cavalry, one Regiment strong. Artillery, consisting of one Battalion and the Central Arsenal Directorate. Engineer, with two Sappers’ Companies. Furthermore, ten battalions of “Skirmishers” were created, consisting of irregular corps personnel. For the first time ever, a Gendarmerie Corps was established, while, in the context of the welfare measures for the Fighters, the “Veterans Company” was established. Concurrently, the Secretariat regarding Military Affairs was established along with the General Staff Officers Corps and the institution of the Army Inspector General.

In the years of King Otto, certain modifications were implemented on the Army Organisation, the most important of which where the renaming of the Secretariat on Military Affairs to Ministry of Military Affairs, with the abolishment of the post of Army Inspector General and the establishment of six Chambers for the management of finance and materiel of the units. Subsequently, the honorary “Phalanx” corps was established along with the “Border Guards” for the guarding of the borders, while concurrently, the National Guard Corps was also established.

In the Ottonian period the development of the army did not reach the desired levels, as the internal situation was still disturbed by revolutions, riots and rebellions, in which part of the army sometimes took an active part. However, the effort made in the areas of organisation, training and equipment was considerable and laid the foundations for the creation of an army on European lines, always within the limits of the newly established kingdom’s limited financial resources.

The Hellenic Army, from 1864 up to the Greek-Turkish War of 1897

In 1863, the organisation of a powerful army, a requirement for the realisation of the Great Idea, was

made a priority with the coronation of George A’.

The new and systematic effort for the reorganisation of the army throughout the fields and the

disengagement from politics and its other obligations in issues of domestic order and security, was finally assumed in 1877. Up to that point, the Organisation of 1833 was in force, with the modifications it had gone through. In the context of this effort, in June 1877, two Divisions were formed. Each Division included a Staff and two Brigades, an Evzones Battalion, the corresponding Cavalry and Artillery detachments as well as miscellaneous Logistics services.

In 1877, it was stipulated that the main portable weaponry of the Army would be the Gras rifle, model 1874 and calibre 11 mm.

In 1884, the French mission under Major General Vosseur was invited to take over the direction of training and the study of the Army Organisation, for three years.

Apart from the new Organization of the Evelpidon School, which was established in 1864, many military schools were organized and operated from time to time for the training of officers and non-commissioned officers in subjects of their competence. Some of these were the Military School of Non-Commissioned Officers, the Training Company, the Preparatory School for Reserve Officers, the Training Battalion, the Preparatory School for Non-Commissioned Officers, the School of Horsemanship and the Shooting School.

The creative effort was cut short in 1880 with the mobilisation declared in light of the annexation of

Thessaly and Arta. It fell behind schedule once more because of the new mobilisation of 1885 which lasted for several months. Apart from the temporary surcease of organisational and training efforts, these circumstances also placed a burden on the state budget with extremely high expenses. Thus, despite the small progress noted, army modernisation did not reach the desired level, resulting in the country being militarily unprepared for the Greek-Turkish War of 1897.

The Reorganisation after 1897 and the Great National Campaign (1912-1913)

The unfortunate outcome of the Greek-Turkish War of 1897, as well as the “Macedonian Question” which arose in the meantime, due to the activities of the Bulgarian Committee, made the need for strong military forces an imperative. The gradual disbandment of new units followed, which had been

formed during mobilisation, as well as the discharge of reserves. Only two divisions were maintained,

headquartered in Lamia and Athens correspondingly, as well as five brigades, while the Evzones Battalions remained temporarily independent.

The most important reforms from 1904 to 1912 mainly pertained to the formation of an army

composed of large units of uniform composition, the reorganisation of the Staff Service, the division of Artillery per type and the systematic organisation of Logistics Services. Furthermore, a Mobilisation Plan was drafted and a Reserve Officers Corps was established.

Moreover, the weaponry was updated with the procurement of new rifles and firearms and the personnel went through intensive training. For this purpose, the French Military Mission was invited in 1911 to greatly contribute to the qualitative and operational improvement of the Hellenic Army. But the greatest of all the preparations was the uplift of the national morale.

The Great National Campaign of 1912-13, which resulted in the liberation of Macedonia, Thrace and Epirus, constituted the upmost success of the Hellenic Army and proof of its capability to respond to the requirements of the times.

The Hellenic Army from 1913 to 1923

The 2nd Balkan War was over with the Bucharest Peace

Treaty (28 July 1913) with Greece securing the largest

part of the territories of Macedonia and Epirus, as well

as the annexation of Crete and the islands of the

Northern and Eastern Aegean.

A year later, when World War I was declared, Greece maintained a stance of neutrality, with the initial

agreement of King Constantine and the Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos. However, after a while,

Venizelos certain for the final victory of the Allies, pushed for the country to immediately join the war at the side of Triple Entente, an estimate opposite to the views of Constantine and the circles of the General Staff regarding maintained neutrality. Thus, the commencement of the National Schism was signalled, culminating in the formation by Venizelos of the Government of National Defence in Thessaloniki in 1916 and the declaration and organisation of the Army Corps of the same name. In June 1917, Greece officially declared the war against the Central Forces decisively contributing to the collapse of the Macedonian Front, in 1918. The conclusion of the conflict at the Eastern Front, but also the end of the Ottoman Empire itself, were realised with the Armistice of Mudros, on 17 October 1918.

Subsequently, Greece accepted the proposal for assignment of troops to Southern Russia, on the side of Entente, against the Bolsheviks, hoping for the support of France regarding the dispatch of the Hellenic Army to Asia Minor to defend the Greek populations there.

The Greek troops unstoppably marched through the soil of Asia Minor from 16 May 1919, while the Treaty of Sevres on 28 July 1920 constituted the official ratification of the Greek claims at the expense of the sovereign rights of the High Porte.

However, in 1921, the diplomatic conditions changed radically in favour of the Turkish nationalists and Kemal Ataturk, who had prevailed at the Turkish interior, moved to the conclusion of agreements with France, Italy and the Soviet Union. The Asia Minor Question sadly concluded with the Turkish counter-attack of 13 August 1922. The Greek troops were obligated to definitive retreat and gradual withdrawal from the Asia Minor soil, while the entry of the Turkish Army in Smyrna, on 27 August 1922, was concluded with acts of violence and the slaughter of thousands of Christians, the pillaging of property, the city’s burning and the uprooting of the Greeks of Ionia. With the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, on 24 July 1923, the war between Greece and Turkey was definitively over, the current borders between the two states were determined and population exchange was imposed.

Inter-war Period up to WWII (1923-1945)

The country’s financial collapse made the Greek state’s regroup a pressing necessity, with the most

urgent matter being the restitution and assimilation of approximately one and a half million expatriate refugees from Eastern Thrace and Asia Minor. The constant interchange of governments, the changes in regime and the frequent army interventions in the country’s political life constituted the intense instability climate which characterised the internal developments from 1923 and up until the country’s joining WWII.

A milestone in the history of military medicine was the foundation, in 1926, of the Military Medicine School. In 1927, in the context of the overall effort to rectify the country, to resolve financial and social issues and to reorganise the army, a bill was passed on issues of recruitment, which mainly aimed to curtail state expenses. The duration of service was fixed at eighteen months for all Arms, while draft evaders, even in peacetime, faced strict penalties.

In 1930, the military facilities in the area of Goudi, which were already being used by the army since the late 19th century, evolved to the largest military complex of the capital and were expanded up to the foothills of Ymittos. Part of the current area of Goudi has been landscaped as a park for recreation and walks, called “Hellenic Army Park”, which is open to the public.

After 1936, in the context of the overall preparation for a possible conflict, the Hellenic Army General Staff, to deal with the lack of uniforms, boots, belts with shoulder straps, items for military camping and other logistics materials, moved to the enhancement of military industry and the development, mainly, of the military factories of the General Army Materiel Depots in Piraeus and Thessaloniki. The Piraeus General Depot operated from 1909 and, up to 1937, was housed in the buildings of the Hellenic Army Academy (Evelpidon) in downtown Piraeus. Then it was decided that it would be reorganised and installed in the area of Drapetsona, in a wide-ranging, new complex of depots and factories able to respond to the requirements, not only of peacetime, but also those of a war. In 1946, the General Army Materiel Depot in Piraeus was renamed to 700 Military Clothing Factory and ten years later to 700 Military Clothing – Footwear Factory.

In the context of the state’s war preparation, in the late 30s, a drafting of an operations plan for the

Hellenic Army began, based on the civilian-military conditions prevalent in the Balkans and the

superiority of the possible opponents in armoured assets and air force. Thanks to the perfect staff

preparation and the clarity of the plan, the simple and laconic signal of the Commander in Chief, in the morning of 28th October 1940, was enough to automatically set in motion the whole war

mechanism.

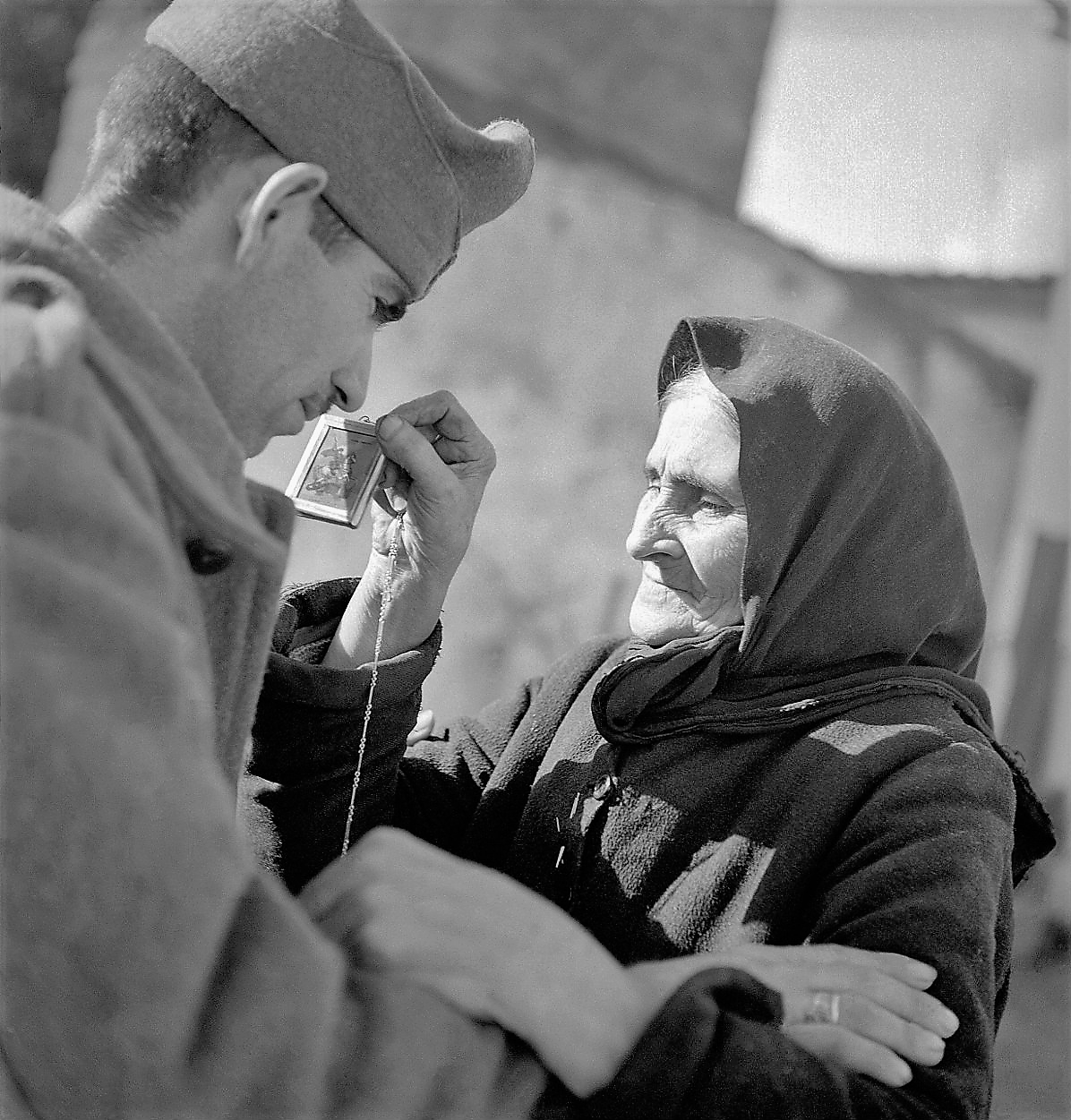

On 28 October 1940, Italy, in the context of implementation of its plans for expansion in the Mediterranean, declared war on Greece. Operations took place at two separate theatres of operations, Epirus and Western Macedonia, with the Pindus Sector as an intermediate connection. Up until 13 November 1940, the Italian troops fell back to defensive formation, waiting for reinforcements. On the contrary, the Greek detachments in Epirus and Pindus retrieved the largest part of the territory, where the Italian intrusion had taken place.

During the second stage of the Greek-Italian confrontation (14 November 1940 – 6 January 1941) the large general counter-attack was conducted, along with the march of the Hellenic Army throughout the Albanian theatre of operations, successively occupying historic birthplaces of Hellenism, like Korce, Permet, Sarande, Gjirokaster and Himare.

Despite the suspension of large-scale operations from 6 January 1941, due to adverse weather conditions and resupply problems in materials and ammunition, the Greek troops managed to occupy the strategic narrow pass of Kleisoura and the heights of Trebeshina, causing severe casualties to the Italians. The capstone of the superiority of Greek troops was the rebuff of the Italian spring offensive, on 9 March 1941, and their firm resistance during the battle of height 731, on 19 March, which signalled the definitive termination of the whole operation. The unfavourable outcome for the Italians of their fiercest and well-organised offensive, definitively overturned Mussolini’s plans for the occupation of Greece, managed a significant blow to the prestige of Italy and the Axis and caused the invasion of the Germans to Greece.

The German troops’ invasion on Greek soil, on 6 April 1941, signalled the commencement of the Battle of the Forts, the four-day struggle at the forts of the “Metaxas Line”, along the Greek-Bulgarian borders. Despite the constant offensives, the fortified defence location could not be penetrated and most of the forts remained impregnable.

However, the rapid collapse of the southern part of the Yugoslavian front and the lack of available forces for the coverage of the left side of the fortification, gave the opportunity to the German 2nd Armour Division to intrude into the Greek territory and then rapidly march to Thessaloniki, which it occupied in the morning of the 9th of April 1941.

The signing of a capitulation protocol and the cessation of hostilities signalled the end of the forts’ struggle, which lasted for a few days. On 10 April, the Greek forces of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace were forced to cut the battle short and surrender their weaponry without having been defeated in the battlefield. Subsequently, the occupation of the Peloponnese and the withdrawal of the remaining British detachments from the country, in late April, signalled the essential completion of the occupation of mainland Greece, while, up until the first fifteen days of May 1941, the major islands of the Aegean and the Ionian, apart from Limnos and Crete, had been occupied. On Crete, the final battle of the struggle of the Greek troops against the forces of the Axis took place, before the complete occupation of the country. Up until the end of the month, the occupation of the island had been completed, despite the fierce defence of the British-Greek forces and the resistance of the whole Cretan people, and in the night of 31 May, after an order by the Middle East Command, the last British detachments departed from the shores of Sfakia.

The struggle against the forces of the Axis went on in North Africa. On 15 June 1941, the HQ of the Middle East Royal Hellenic Army was established, with the goal of commanding the Army under formation. Progressively, the I Infantry Brigade and the I Field Artillery Regiment were formed. The highpoint was the participation of the Hellenic Army in the second Battle of El Alamein (23 October – 5 November 1942), where two emblematic military leaders were the protagonists, Erwin Rommel and Bernard Montgomery.

Apart from North Africa, the Hellenic Forces formed the Sacred Band in Palestine, in September 1942, with the main mission of conducting mostly raiding actions. Its war action commenced at the North Africa front, in late 1942, with the participation of small detachments in operations reaching Cyrenaica. It took part in missions of surprise raids in the Aegean and the fruitless operation for the liberation of Samos and the neighbouring islands. As a Raiders Squadron, in collaboration with British Units, it successfully executed numerous daring raiding operations of wide scale, which resulted in the liberation of the islands of the Aegean. Moreover, it constituted the forerunner of the Hellenic Raider Forces and current Special Forces.

On 31 May 1944, the formation of the III Hellenic Mountain Brigade was decided, at camp Ansariye in Lebanon. It was then transferred to Tripoli in Lebanon, where, by the end of July, its training in mountain fighting was completed and it was prepared with the goal of participating in the allied operations in Italy, aiming to break through the so-called “Gothic Line” of the Germans.

In August 1944, the brigade was transferred by ships to Taranto – Italy and fell under the New Zealand

Expeditionary Force of General Freyberg. On 3 September, it was assigned to the 5th Canadian

Division and two days later it entered the zone of operations and participated in the fight with its

artillery. After the beginning of operations for the occupation of Rimini, on 14 September, the brigade

occupied the Rimini airfield. Subsequently, on 20 September 1944, its main offensive for the occupation of the city of Rimini was absolutely successful and so it assumed the honorary designation “Rimini Brigade”.

After the gradual withdrawal of the occupation troops (Germans and Bulgarians) from Greece, in October 1944, the Greek Government commenced the effort of the country’s reconstruction. In cooperation with the British military detachment deployed in Greece, it decided to rapidly form National Guard units for maintaining order and the subsequent organisation of regular troops, whereas after a while, detachments of the Sacred Band, the ΙΙΙ Hellenic Mountain Brigade and

echelons of the Hellenic Army General Staff arrived in Athens. It was decided that the ΙΙΙ Hellenic Mountain Brigade would be utilised as the core for the reorganisation of the army, the expeditionary force would be increased, the National Guard would be limited to solely military duties and that it would be transformed into a regular army, as soon as possible.

At the same time, in 1945, the Ministry of Military Affairs was reorganised, including the Hellenic Army General Staff and the General Directorate of the Ministry of Military Affairs. Its mission was to make decisions regarding the force, organisation and formation of the army, the distribution of credits and materiel, training, mobilisation and supply plans and the overall required measures for the defence and the internal security of the country.

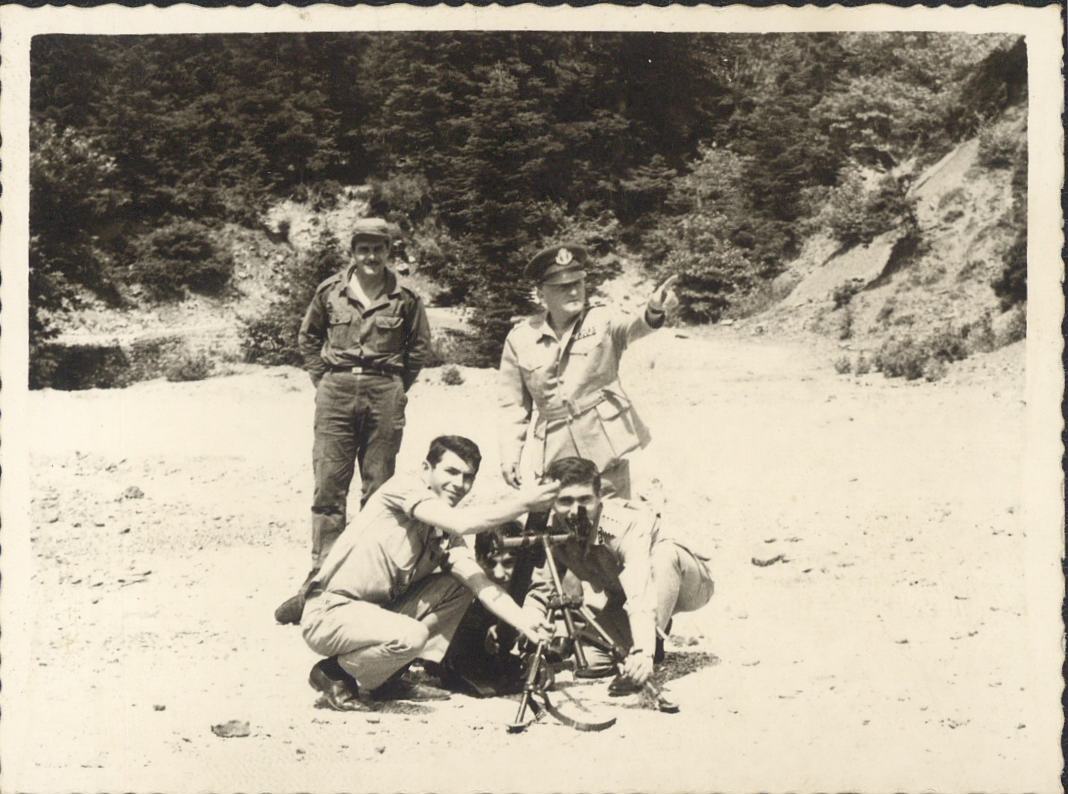

The period after WWII (1945-1955)

In June 1946, just a few months after the commencement of the Civil War, the new army

organisation was realised in Arms, Corps and Services, which, among others, stipulated the development of two new Arms, the Signals Corps which had been established since February and the Armour which would join the Cavalry.

The formation of the Signals Corps into an Arm was deemed necessary after the war, due to the increased requirements in organisation and securing of army communications and the conduct of Electronic Warfare. For the fulfilment of its mission, the Arm was organised into Signals commands and units, which existed in every major formation, from the Hellenic Army General Staff to the divisions. Furthermore, for its better organisation, in 1946, the Signals Directorate of the Hellenic Army General Staff was established, superior from and responsible for the Signals Training Centre and the 487 Signals Battalion of the Hellenic Army General Staff.

The development of the second new Arm, Cavalry-Armour, constituted a decisive step towards the enhancement of the combativeness of the Hellenic Army. In May 1946, the first 52 “Centaur” type British main battle tanks arrived in Greece. They were stored at the Armour Training Centre, where they remained for more than 15 months, until eight officers dispatched to the British Armour School in Egypt, in February 1947, completed their training.

In September 1946, the army essentially assumed the responsibility to conduct operations against the Democratic Army of Greece. In early 1947, the first 40 companies of Mountain Raiders were formed. After the initial successes of the Raider Units in the battlefield, their reorganisation was put on track in June 1947. All the Raider Units were considered, from that point on, an integrated force called “Raider Forces” and immediately a plan was drafted for their regular utilisation in battle. Up until February 1948, the Commands had been renamed to Raider Squadrons and fell under the newly established “Raider Forces Command”, under the 1st Army, headquartered in Volos.

On 7 March 1948, the Dodecanese were officially annexed to Greece. Already, however, the force of all the state institutions had been expanded to the islands by law, the secondment of reserve officers and privates had been stipulated and the competency of the Athens Court-Martial had expanded territorially to the Dodecanese.

The Dodecanese were liberated by the Sacred Band and were delivered to the charge of the British along with the surrender of the German Garrison, on 8 May 1945. Their administration was temporarily taken over by the British Military Command of the Dodecanese. In late September 1945, the Greek Government, so as to facilitate the British Command in its work, established the Greek Military Mission of the Dodecanese for the smooth preparation regarding the integration of the islands to the Greek state, as well as the resolution of day-to-day issues which concerned the inhabitants, like healthcare, education, welfare, rebuilding, in cooperation with the British.

During approximately the same period (1946-1949) the Greek Civil War took place, meaning the armed conflicts between the Democratic Army of Greece, which was under the political guidance of the Communist Party of Greece, and the National Army, which was under governmental control. The official commencement of the war was signalled with the surprise assault of armed detachments against the gendarmerie station in Litochoro-Pieria, at the night of 30/31 March 1946. Corresponding attacks against military garrisons in border cities, townships and villages followed.

In 1947, the National Army assumed offensive action, initially with actions to hem the opponent in and subsequently with clearance operations per geographic area. The conflict spread around in Central Greece, Thessaly, Macedonia and Thrace. In 1948, the Democratic Army was at the peak of its might, since it reinforced its bases on Grammos and Vitsi with defensive fortifications and assets for battle support. The National Army maintained its offensive tactics with coordinated actions and even more forces. That year, the operations “Charavgi” in Central Greece (15 April-26 May) and “Koronis” in the wider area of Grammos (20 July-22 August) were conducted. From early September up until December, the conflicts on Vitsi were constant, while from late 1948, the operations intensified in the Peloponnese too.

In 1949, the abandonment of surrounding tactics and the conduct of night operations and ceaseless pursuit by the National Army, surprised the leadership of the Democratic Army and signalled the change of the situation in favour of the former. The final clearance operations “Pyrsos A” on Northern Grammos (2-8 August), “Pyrsos B” (10-16 August) on Vitsi and “Pyrsos C” on Grammos (24-30 August) were absolutely successful for the National Army. The occupation of the Kamenik height (currently “2nd Lieutenant Panagiotou I.”), at the night of 29th August 1949, signalled the definitive defeat of the Democratic Army and essentially the end of the war.

With the goal of its greatest possible integration to the newly established international institutions, in November 1950, Greece sent the Greek Expeditionary Force in Korea, in the framework of the military intervention of the United Nations in the region, after the surprise invasion of the North-Korean forces in the territory of the Republic of Korea (South Korea), on 25 June 1950. Thus, Greece significantly backed the request for its accession to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. The final accession of Greece to the North Atlantic Alliance, in February 1952 (along with Turkey), and the signing of the bilateral agreement with the USA for the installation of US bases on Greek soil, in October 1953, solidified its position in the Euro-Atlantic security system.

On 20 August 1954, Greece’s appeal to the UN for the exercise of the right of the Cypriots to self-determination signalled the internationalisation of the Cyprus Question and on the other hand it inaugurated a period of crisis in the relations of the country with its western partners. At the same time, it gave new rise to tensions in Greek-Turkish relations, which peaked with the persecutions of the Greeks of Constantinople, in September 1955.

1955-1974 Period

In 1959, the London and Zurich Agreements, although they paved the way for the independence of Cyprus, concluded a diplomatic compromise which included the waive of the claim regarding the unification of Cyprus with Greece, but also the exclusion of the possibility of dividing the island.

In June 1959, the submission of request by Greece for its connection with the newly-established European Economic Community (EEC) indicated the European orientation of the country, aiming to consolidate the democratic institutions, the modernisation of economy and society and the reinforcement of its position in the regional and international system. In July 1961, the conclusion of a final agreement for the connection of Greece with EEC in the form of customs union –the first of its kind in the history of European unification– constituted the first step for its full accession to the Community.

Domestically, the elections of 1961 led to the re-emergence of political passions, with the country, since then, going through a phase of intense polarisation and institutional crisis. In 1965, the rupture of the king’s relations with the prime minister at the time, the resignation of the government and the period of political destabilisation which followed (Iouliana) indicated the limits of the political system after the civil war, paving the way for the military coup of the 21st of April 1967. With the dictatorship taking control, the country entered a period of international isolation. With the exception of the USA which maintained a neutral stance, Greece became the unwanted ally of the West, a fact which led to the suspension of the procedures for its accession to the EEC and its exit from the Council of Europe.

The systematic policy of Turkey’s disputes and claims at the expense of Greece’s sovereign rights, from the early 70s and, at the same time, failure to regulate the problems regarding the proper function of the Republic of Cyprus, after November 1963, which resulted in escalation, with the confrontation between the dictators and its President, the Archbishop Makarios, which caused the deterioration of the Greek-Turkish relations, with the Cyprus Question testing both countries’ limits. On 15 July 1974, there was an outbreak of a coup which aimed to overthrow Archbishop Makarios and to unite Cyprus with Greece. This provided Turkey with the ideal false justification to launch a military intervention on Cyprus, on 20 July 1974, appealing to the violation of international treaties and the constitution of 1960.

Under the burden of the national disaster, the dictatorial regime in Greece collapsed. The responsibility for the exit of the country from the crisis and the restitution of democracy was once again in the hands of the politicians.

The peak of the Cold War in the 60s, the intense defence problems caused by the military dictatorship (1967-1974) and the Turkish military threat, especially after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, imposed a constant and increased military readiness. Greece, despite the challenges, remained a place of peace and stability, preserving concurrently a powerful military factor for the safeguarding of national security.

The 4-year attendance at the Hellenic Army Academy (Evelpidon) was institutionalised in 1961, along with the pre-selection in Arms and Corps before admission. In 1982, the Hellenic Army Academy (Evelpidon) was relocated to its new, modern installations in Vari-Attica. In 1991, the attendance of women in the Academy was institutionalised. After their graduation they would be placed in the Corps of Supply-Transportation, Ordnance and Technical, at the rank of 2nd Lieutenant.

1975-2020 Period

The collapse of the military dictatorship, in July 1974, signalled the restitution of the democratic legality and the definitive transition of Greece to regularity (Third Hellenic Republic).

From the first days of the political transition, the management of the crisis with Turkey was the focus of the Greek foreign policy. The passive neutrality policy adopted by the USA and ΝΑΤΟ, after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, caused Greece’s withdrawal from the military wing of the North Atlantic Treaty, in August 1974. The first governments of the political transition developed a multifaceted foreign policy, which included the adoption of a new policy in Eastern Europe, the establishment of closer relations with the Arab world, the initiative for the institutionalisation of multilateral Balkan cooperation and the shaping of a more balanced relation with the USA and, finally, the country’s return to the military wing of NATO in 1980.

The recommencement of procedures for the accession of Greece to the European Economic Community, in 1976, resulted in its accession to the EEC as full member on the 1st of January 1981. Years with satisfactory economic development and strengthening of institutions followed.

In the field of Greek-Turkish confrontation, in March 1987, Greece had to face once more a serious crisis in its relations with Turkey. The decision of Turkey’s National Security Council to dispatch a research vessel named “Sismik” in the Aegean, in the area east of Thasos, almost resulted in a conflict between Greece and Turkey.

The collapse of real socialism in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union in the late 80s, although it signalled the end of the Cold War and was the starting point for global collaboration and disarmament, also gave rise to new oppositions. In the 90s, the breakup of the multinational state of Yugoslavia took place and thus various nationalistic claims re-emerged, especially in the area of the Balkans. The effort of national cleansing in these areas, as well as the need for restitution of regularity in various points of the planet, led to the activation of the international community. In this context, Greek military detachments participated in international peacekeeping missions (Somalia, Kosovo, Afghanistan).

In January 1996, the Imia crisis, the actual dispute of the Greek sovereignty, on national soil, by Turkey, with the excuse of the stranding of a boat on the rocks of the same name, was the last significant event of the Greek-Turkish opposition in the 20th century. In the following years, Greece has made substantial claims for the title of a powerful stabilisation factor in the Balkans and the Eastern Mediterranean, emphasising respect to international law and the democratic values.

In late February 2020, the country had to face, once again, the Turkish provocativeness. The decision of the Turkish Government for unilateral opening of its land borders with Greece, caused the massive and guided influx of refugees and immigrants in the area of Evros. A few months later, in August 2020, the sea research operation of the Turkish vessel “Oruç Reis” within the Greek continental shelf, accompanied by Turkish warships, constituted one of the most critical events of the Greek-Turkish opposition since 1974.